England's Doom - Part III

Harold's Norman Expedition

Harold’s expedition to Normandy in 1064 is a tragic tale. England’s noble protector found himself perilously placed as he struggled to rescue kin. Machiavellian machinations, the consequences of which echo throughout history’s halls, characterise his time at William’s court. Two great men played political chess with a kingdom at stake: ending in personal betrayal and bloody strife. A tragedy worthy of Ancient Greece’s auditoriums or Shakespeare’s hallowed pages! As with the succession question much mystery clouds this event; here Bayeux’s Tapestry comes into its own. The key questions to answer are: why did Harold set sail? What did he swear to? And how did each party view the oath?

Contemporary English writers refuse to record Harold’s expedition. At the time, the kingdom’s foremost earl, absent for the best part of a year, caused great concern. Norman writers differ in their accounts, Wop provides a detailed description based on recollection and hearsay. The BT, woven just over a decade later at the behest of William’s half-brother Bishop Odo of Bayeux, offers a mixed Anglo-Norman perspective. Later writers from England and Normandy offer important information too, being bold enough to mention events contemporaries from either race shied away from. Having just triumphed over Wales, earning England’s acclaim, Harold is supremely confident. His gaze turns southwards to Normandy, believing the time opportune to launch a long-overdue endeavour.

Contemporary Norman sources would have us believe Harold travelled to Normandy to solidify Edward’s earlier bequest to William. As we have seen, Edward’s eye looked elsewhere as did England’s elites. Nor is Edward’s power sufficiently potent in 1064 to rename William or to order Harold to deliver the promise. Eadmer claims the expedition was to recover Harold’s kin Wulfnoth (Godwine’s youngest son) and Hakon (a nephew; Swegn’s son). The pair were given as hostages during the revolutionary and counter-revolutionary events between 1051-52. Why they fell into William’s hands can be deduced. The Bayeux Tapestry fails to explain why Harold departed but it draws on Canterbury’s tradition and that of Wop. Considering the claims of later men, at the time the issue remained so contentious it was better to leave the meaning open to interpretation.

‘King Edward’

Wop claims the pair were given as surety of his duke’s succession; Eadmer claims it was to ensure good faith during negotiations between Godwine and Edward. If they were given as hostages to ensure William’s claim, why did the rest of England’s magnates not provide hostages? The two hostages came from the two men in Godwine’s family whom Edward distrusted, Godwine and Swegn. Considering William’s case was no longer valid in English eyes by 1064, if Poitiers’ claim is true, they should have been returned, meaning Duke William held them longer than due. If it is not true, the same reasoning still applies. The pair were unlawfully detained. Amongst contemporaries Duke William held the reputation of a man capable of unlawfully detaining men indefinitely, doing so for expediency’s sake or until he acquired the desired result. Wulfnoth only gained freedom in 1087, if only briefly. When Archbishop Robert fled London in 1052, his party killed many young men whilst passing through London’s eastern gate, taking the pair to Normandy. Edward’s plans stood in ruin, enraged at Godwine’s gains, he rashly sent the pair with Robert. By now the city switched to Godwine’s camp, attempting to bring Robert to ‘justice’ and free the hostages.

Of the pair, Eadmer is more reliable and in akin to contemporary accounts. Eadmer consulted Bishop Aethelric (Harold’s uncle) when writing the ‘Life of Dunstan’, as such the pair likely discussed Harold’s expedition at some point. Either off-topic during his known consultation, or specifically when he wrote his Historia Novorum. Eadmer also corresponded with Prior Nicholas of Worchester, the favourite pupil of Harold’s close friend Saint Wulfstan, a man whom Harold turned to for counsel and spiritual guidance. Eadmer enjoyed access to insider information, and could consult older monks, known to possess close relations to Aethelric. Eadmer’s manuscript must have been acceptable to his Norman superiors at Christchurch too. Traditions from which the BT drew, stem from Christchurch’s close relationship to the Godwines. Some of the seamstresses are aristocratic widows, perhaps their husbands accompanied Harold to Normandy.

Apparently, Edward reluctantly acquiesced to Harold’s expedition but foretold only harm would come of it for the English.[1] Harold rejected Edward’s advice to send messengers in his stead. Wace claims Edward ‘openly refused him permission’ to treat with William and to cross over to Normandy. Edward knew the duke to be ‘very astute’, and quite capable of tricking the earl.[2] All these claims reek of hindsight but chivalry met its match in cunning conniving. Each later writer relays how contemporaries saw the expedition as hubristic and against royal will. Wace partially relied in Eadmer’s information, himself relying on his elders. William was viewed with suspicion, especially after the murder of Walter of Mantes, but not outright hostility as Harold believed in the possibility of success, taking courtly gifts of hawks and hounds for the hunt. William’s persistent interest in the crown must have been unknown; Norman charters only briefly reference kinship to Edward. The truth to these writers is born out in the Tapestry’s depiction of Harold’s return to England.

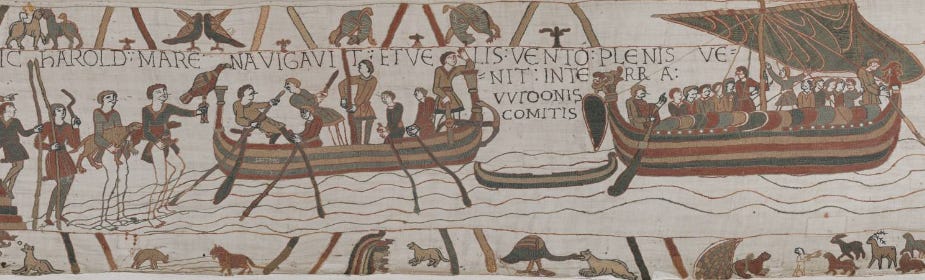

Harold departs for the continent then steers his ship.

‘Here Harold crosses the sea’

Whatever the exact truth, Harold gambled without profit. Poor weather forced Harold to land at Ponthieu, whereat Count Guy I imprisoned him, demanding ransom for England’s earl. Guy’s action is strange, why did he feel secure enough to seize England’s foremost man? The scenes depicting the landing and journey suggest tension between parties, with gifts given or seized. After the battle of Mortemer in 1054 Guy swore fealty to William. Norman writers insistently portray Guy as acting independently, depicting the duke as Harold’s saviour. Help soon arrived from Duke William, who, according to Wop, used gifts and threats to secure Harold’s release, thereby indebting Harold to him. Several features of the scene attract interest.

‘Where Harold and Guy confer’

Two Englishmen point at a Frenchman between them, who himself points forward at Harold and another Englishman. Englishmen have moustaches and long curled hair, status symbols of Anglo-Saxon warrior aristocracy. Frenchmen do not, preferring shortly-cut hair and clean shaven cheeks; reformed Christian aesthetic. Disagreement arose, the details of which we will never know, and for which accusations flew. In the centre Harold presents his sword to an enthroned Guy. Presentation of one’s sword can either be a sign of submission or friendship. Harold deploys his rhetorical skills to defend himself and his companions. Count Guy stands in judgement over them, imprisoning them for some offence, real or cunningly contrived.

The figure on the right is often interpreted as a Norman or English messenger who brings William news of Harold’s imprisonment. However, the figure bares no resemblance to the Englishman who is shown to inform William of Harold’s predicament. On the other hand, it may depict Norman influence at Guy’s court, directing his decision to imprison Harold. Contemporary chroniclers believed William was able to exert influence into foreign courts, and his efforts during the 1050s and 1060s centred on curtailing neighbours. This is not as far fetched as it might seem. The brother of William’s chief advisor presided over the church of Bosham, from where Harold departed. Thus, William soon knew of Harold’s plans to depart for Normandy. Below Guy receives gifts from William’s envoys, his attire differs greatly from the previous scene. Before he is drably attired, now his gown is of higher quality and pattern, he holds a highly prized Viking battle axe too.

‘Duke William’s messengers came to Guy’

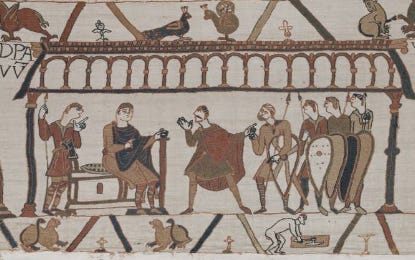

Upon Harold’s arrival at William’s court an audience took place. Typical to trend, the BT fails to substantiate. The tapestry’s depiction can be deciphered in two respects. Norman: here Harold reaffirms Edward’s wish for William’s succession. Non-Norman: Harold thanks William for his freedom then explains the cause of his expedition. Afterwards William asks Harold to accompany him on his coming campaign, promising to answer the earl’s request when they return. Orderic Vitalis simply states the duke made Harold stay in Normandy for some time.[3] Harold could do little but acquiesce, Harold was indebted to him. William’s continued desire for the crown was unknown to those outside his close circle and select Normans in foreign courts. Otherwise, why would Harold journey into the clutches of his competitor? William showed himself perfectly friendly to Harold despite his true intentions differing. Harold, aware of the duke’s politique praxis, soon knew he miscalculated this expedition; he resolved to show William his words and deeds do justice to his reputation.

Duke William of Normandy receives Earl Harold at his palace.

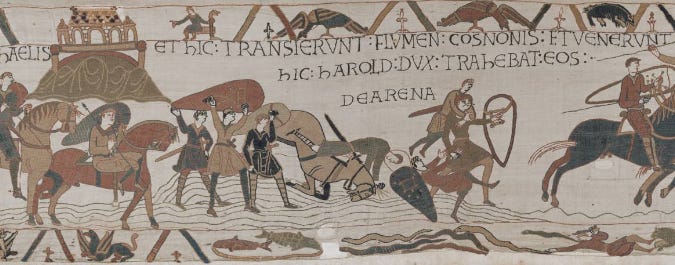

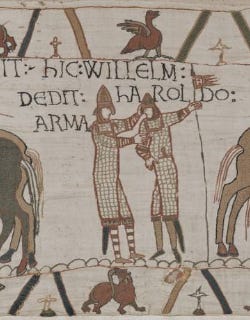

Our two princes set off for Brittany to quell Count Conan II in a drawn-out campaign of castle-building and siege warfare. Each man assessed one another’s traits. Harold impressed the duke for his courage and counsel. Norman sources sing Harold’s praise; heroically, single-handedly saving several Norman soldiers. William confirmed Harold posed the greatest threat to his ambitions, messengers and bards all spoke truthfully. Likewise, Harold witnessed first-hand the duke’s resolve, cunning, and military might. William’s Norman campaign fizzled out without significant strategic success. Despite so, William faced off against Brittany and Anjou, showing a skilled strategic mind and revealing the efficacy of Norman warfare to Harold. The duke had not won, nor had his losses been dear, confirming the duke’s resolute reputation to Harold. Each man developed respect for the other’s character. After the campaign William gave Harold arms.

‘Here Duke Harold dragged them out of the quicksand’ at Mont-Saint Michel. Even William’s priest admits Harold ‘was such a man as poems liken to Hector or Tumus.’

Harold swore fealty to William as his lord, swearing to uphold his lord’s interests. By the eleventh century men often possessed more than one lord, Edward remained Harold’s liege-lord, loyalty to whom trumped all others. Harold’s fealty and oath came under duress, no illusions clouded the earl’s judgement as to his fate if he refused. Then William voiced his true intentions. At Bonneville-sur-Toques the duke told Harold of his unbroken desire to succeed Edward and his belief the 1051 offer remained valid. A shocked Harold was thrown off-balance. The duke dangled his kins’ freedom before him, alongside the earl’s own. Just as he did to Count Guy a decade before. Wop takes special care to emphasise Harold swore the oath ‘clearly and of his own free will’, contemporaries criticised the oath’s coerced nature.[4] As is oft the case, the opposite of whatever the priest claims is where truth lies.

‘Here William gave arms to Harold’

Wace claims the duke tricked Harold to obtain a holy oath, covering the relics on which he swore. Only afterwards did the duke pull the brocade up, revealing the relics beneath; Harold turned pale with penance, realising the scale of his folly.[5] Writing a century after the event it is not apparent whether Wace’s addition is based on fact or fantasy. It does indicate tradition survived in Normandy concerning the duke’s duplicity in obtaining Harold’s oath. Saint Jerome is referenced in later legal texts, when Anglo-Saxon and Norman custom are under synthetisation, a valid oath required truth, justice, and impartiality as its companions, lacking these it is invalid and perjury.[1] Harold’s lacked all, its companion is coercive cunning. The same text decrees no oath is to be kept if a wrong is promised. The tapestry offers no details of the oath’s content. William of Jumieges, writing closest to the event before criticism to William took more substantial form, probably presents the closest picture to the truth.

All three French writers who mention the oath fail to agree on the details, reflecting the changing needs of their patron and genuine confusion surrounding the ceremony. The tapestry simply states Harold swore an oath. Due to contemporary criticism Wop lays out the entire oath as his duke understood it. Harold was to serve as the duke’s representative at Edward’s court; to use his wealth and influence to ensure William ascends to the throne; Dover was to garrison a detachment of knights. Harold was to pay for their upkeep, Norman soldiers were to be established in other locations.[6] Memories of 1051-52 flashed through the earl’s mind. Wop claims these terms are those which were sworn thirteen years before.

‘Harold made an oath to William’

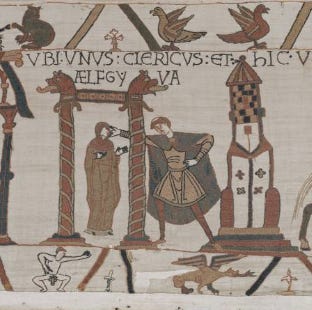

Certain writers mention marriage to seal the arrangement, with Harold given the hand of William’s daughter, a senior Norman noble received like from Harold’s sister. Neither betrothal concluded with marriage. An earlier scene is typically taken to denote it. ‘Aelfgy’ is slapped by the priest as an obscene figure features below. Either Aelfgifu (Harold’s sister) or Adeliza (William’s eldest daughter), likely the former as the scene seeks to besmirch the reputation of the woman. Which could be a Norman or English input depending on how one interprets it. If Norman, the woman was below Norman aristocracy and guilty of sexual impropriety. If English, guilty of betrothal to foreign conquerors. A third option presents itself, the women is Aelfgifu of Northampton, Cnut’s second wife and mother to King Harold I. Wop associates Harold Godwineson with the murder of Alfred to besmirch his character.

‘Where a clerk and Aelfgifu

In one sense, Harold’s expedition achieved its aim. William released Hakon to Harold’s care. Wulfnoth would be released once William inherited the throne by Harold’s hand. William viewed the oath as morally binding but had little faith in Harold’s reliability. Neither man understood the oath in the same manner, nor its actual significance. An oath under duress is not binding, one could rescind it, atoning before God. Goscelin reflects Harold was liberal with oaths, he makes the point in connection to Northumbria’s rebellion against Tostig, whereby Harold cleared his name by oath. The same writer commends Harold’s ability to avoid ambushes in Gaul, nor to be deceived by proposals from French princes. Certain contemporaries saw his survival in this perilous situation as a feat of great skill.[7] This portion of the text comes before 1066, only afterwards did men truly appreciate the consequences of it. In 1064 criticism met Harold on England’s shores, Goscelin felt it his duty to defend a man whose characteristics he deemed a worthy model for posterity.

When Harold returned to England Edward scolded him for ignoring his advice and for compromising himself and the kingdom. The tapestry shows all four men to be gesticulating, three of whom point at Harold, two of whom hold axes, indicating the scale of his scolding. Head low with arms outstretched, Earl Harold placates submissively before King Edward. Edward struck down Harold’s reputable name. Pride preceded Harold’s fall, with him went England’s destiny. This scene offers the most promising evidence that the mission did not aim to consolidate William’s claim. Why would Edward scold the man who went above and beyond to bind himself to William’s ascension? Instead, what we see is Canterbury seamstresses depicting an English account.[8] Harold’s actions affronted Edward’s authority and the aristocracy’s own too. Despite the expedition’s calamity England was relatively safe. William appeared an overly ambitious jumped-up bastard prince; besides, oaths made under duress were not morally nor legally binding. Harold need not adhere to the oath.

‘He came to King Edward’

William struck a hard bargain; Harold came out the lesser man. The duke obtained moral dominance to justify invasion, albeit a weak one which only eventually bore fruit through conquest, papal christening, and in posterity. William undermined Harold’s position to posterity, the earl is forever remembered as a perjurer. At the time all was open to interpretation, the sword proved the deciding factor. We do not know whether Harold cleared his name. Logically, he rescinded it as soon as possible as rejecting the oath would be the first step in ritualised apology for Harold’s return to Edward’s favour.

When Harold fell at Hastings God judged his cause unworthy, the earl earnt infamous reputation amongst Medieval men. To Battle Abbey’s chronicler Harold, a ‘certain perjured slave,’ seized the crown.[9] Breaking his word before God and men. The politics practiced by Godwine’s family of subtle, patient compromise failed against the cunning machinations of Duke William. The duke raised an unjust claim to the throne, to advance which he cunningly coerced Harold. It marks the first crowning success of the Conqueror, he gained even if Harold broke his oath, using it to rally his folk and lobby the pope. Even so, William was well aware of England’s power and wealth, in 1065 fortune shone fortunately on the duke when England’s ruling class divided in civil strife.

https://www.bayeuxmuseum.com/en/the-bayeux-tapestry/discover-the-bayeux-tapestry/explore-online/

[1] Eadmer, Historia Novorum in Anglia, (The Cresset Press, 1964), p. 6.

[2] Robert Wace, Roman de Rou, (The Boydell Press, 2004), p. 153.

[3] Orderic Vitalis’ edition of the Gesta Normannorum Ducum in HN, p. 161.

[4] William of Poitiers, Gesta Guillelmi, p. 71.

[5] Robert Wace, Roman de Rou, pp. 154-155.

[6] William of Poitiers, Gesta Guillelmi, p. 71.

[7] Vita Aedwardi Regis, pp. 51 – 53.

[8] In Kent, due to its close ties to Godwine’s family, local knowledge of the event survived. After the conquest English monks still managed to update chronicles with dissent, criticising Norman rule, it is reasonable English seamstresses followed suite.

[9] The Chronicle of Battle Abbey, p.1 https://archive.org/details/chronicleofbatte00batt/page/n19/mode/2up

[1] Leges Henrici Primi, 5, 28, (Oxford Medieval Texts, 1972), p. 95.